The Triple Gem, or “Pra Ratanatrai” in Thai (Pra refers to “high” or “sacred” things, Ratana means gem,and Trai means triple) is the term used to refer to the three objects of Refuge taken by all Buddhists.

When you become a Buddhist, you will be asked to take refuge in the Triple Gem as part of your Initiation process, and (hopefully), in most cases, will receive a teaching on the meaning of what the triple Gem represents in Buddhism. This article intends to explain the basic importance of paying reverence to the triple gem, and the reasons why they are seen as so important by Buddhists of all traditions and lineages.

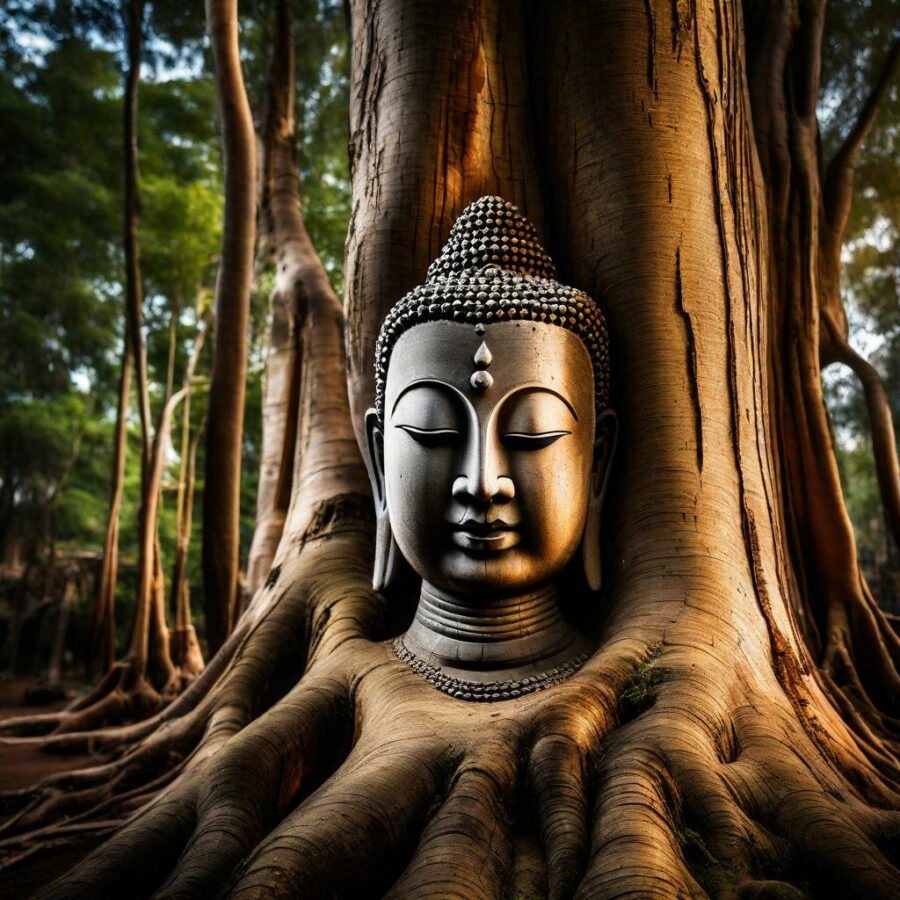

Symbolic Image representing the Triple Gem

The three objects of Refuge are these;

- The Buddha

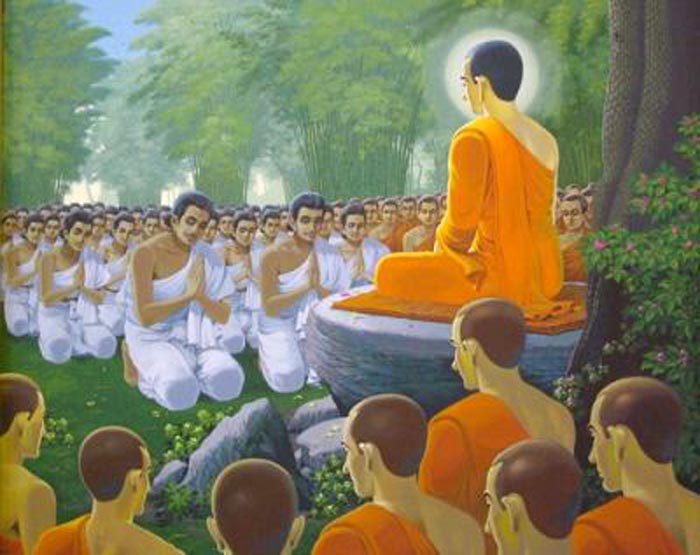

- The Dharma

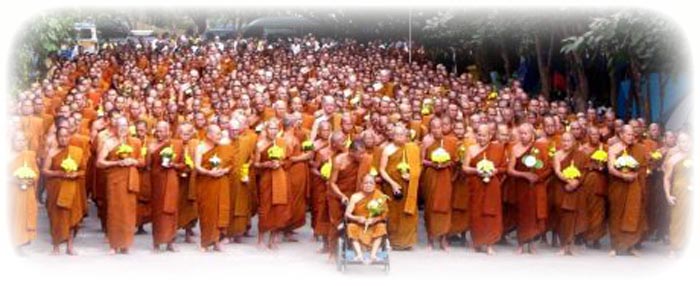

- The Sangha

These three objects are seen as the essential core elements which keep the Buddhist faith in existence, and are thus considered to be the source of inspiration in the practise which leads us to Enlightenment and release from further suffering in the Realm of Causal Existence (Becoming and Passing away – all things are impermanent, have a beginning and an End, which leads to dissatisfaction).

For this reason, a Buddhist takes refuge in the Triple Gem until reaching Enlightenment.

This is normally chanted to oneself whilst bowing three times before the image of the Buddha in the Shrine, or even mornings before beginning the day and night times before sleeping at home.

This is normally performed using the Pali language. The chanting goes like this (Thailand phonetic pronunciation);

- Puttang Saranang Kajchaami (I take Refuge in the Buddha)

- Tammang Saranang Kajchaami (I take Refuge in the Dhamma)

- Sangkhang Saranang Kajchaami (I take Refuge in the Sangha)

Then the same again with the word “Tudtiyambi” as a prefix – which means “for the second time”

- Tudtiyambpi Puttang Saranang Kajchaami

- Tudtiyambpi Tammang Saranang Kajchaami

- Tudtiyambpi Sangkhang Saranang Kajchaami

Then the same again with the word “Dtadtiyambi” as a prefix – which means “for the third time”

- Dtadtiyambpi Puttang Saranang Kajchaami

- Dtadtiyambpi Tammang Saranang Kajchaami

- Dtadtiyambpi Sangkhang Saranang Kajchaami

Alternatively, in other countries, the words are spelled like this;

- Buddham saranam gacchāmi – I go for refuge in the Buddha.

- Dhammam saranam gacchāmi – I go for refuge in the Dharma.

- Sangham saranam gacchāmi – I go for refuge in the Sangha

The reason why all of these three aspects are seen as equally precious, is the fact that;

If there was no Sangha (monks), then the Dhamma would not be able to reach us, for it is the monks who are the living embodiment of the teachings (Dhamma), and it is they who speak the teachings to us and write books for us, and it is they who propagate the practice in the present so that it may still continue in the future.

The Dhamma is the truth of all things in the Universe, always was, is and shall be valid, and is thus the true source which can be uncovered or revealed, enabling our Enlightenment. The Dhamma is the direct cause of our Enlightenment, and is synonymous with the practise.

The Buddha is the being who became Enlightened (knowing the Dhamma in it’s entirety), and is the one who expounded the Dhamma, revealing it to us, so that we could know it and learn to abide by it, using it as a tool to attain Enlightenment with. Without the Buddha, we may never have been lucky enough to encounter the Dhamma, and therefore, the Buddha is seen as the source of the existence of the Dhamma teachings on this planet. Without him, the Dhamma would indeed still be existent, but it would be invisible, unheard of and unknown to Humans, and perhaps the Devas as well.

Important Notes;

The Buddha did not invent the Dhamma, the Dhamma is the true nature of all things in Existence (this is in fact the meaning of the word Dhamma – “nature of things”).

The Buddha even said that the Dhamma existed before he found it, was always true, is now in the present also true, and will still be true in the future, regardless how long a time passes. The Dhamma is the Universal laws that apply to the physical world, and also the non physical world (emotional, mental, spiritual) and these rules and laws apply to life, becoming and all things in existence. They are pure, and unchangeable. The Dhamma teaches that all things are impermanent and changeable, but in fact, the Dhamma that refers to the laws which govern existence itself never changes. The fact that all things are impermanent was true then, is true now, and in the future will still be true – this is an unchangeable truth, and that is what we call a “Dhamma”.

This is of course seemingly self contradictory to say all things are changing, but that this fact is unchangeable.. but this is one of the perplexities of Dhamma when seen from our unenlightened perspective. Once the basic principles of Dhamma have been grasped however, these perplexities disappear and the practitioner ceases to wonder about the self contradictory concepts which occur when attempting to explain the limitless with a limited tool such as Human language.

Reference Links;

Wikipedia – Three Jewels

How to Chant Namo Tassa